Columns By Category

Popular Articles

- THE REALITY OF TACKY AND SAM SHARPE

- PLEASE DON’T BETRAY US AGAIN POLITICIANS

- CRY, MY MURDEROUS COUNTRY

- MODERNIZING THE PNP: VERSION.2020

- IS THE EXCHANGE RATE ON TARGET OR IS IT A WHOPPER?

- CARICOM: BEACON OF DEMOCRACY OR COWARDLY DISGRACE?

- DEMOCRACY PREVAILS IN THE UNITED STATES

- THE CRIME STATISTICS SPEAK FOR THEMSELVES

- PETROJAM, OIL PRICES, AND THE $7 TAX

- Kevin O'Brien Chang | Brains, not brutality – smart(phone) crime fighting

- TERRORISM IN JAMAICA

- STOP CURRENCY CRISIS TALK

- 'CASTIGATED KD' AND THE 9 YEAR WONDER

- GET PAST MERE TALK ON DONS AND GARRISONS

- LOW VOTER TURNOUT MYTHS AND ELECTION PREDICTIONS

- HOW GREAT CAN BROGAD BE?

- PNP WAS SOCIALIST FROM THE START

- AN AGE AND GENDER RE-ALIGNMENT ELECTION?

- Most influential Jamaican of 2010-2019?

- NO GAYLE, NO RUSSELL, NO TALLAWAHS

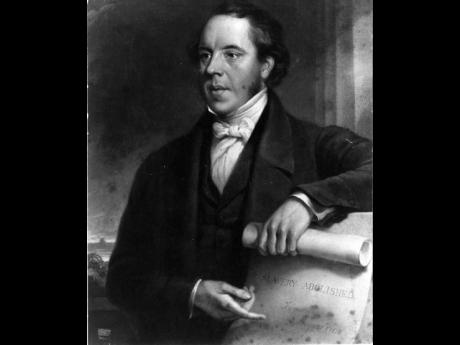

William Knibb - The friend of slaves

- 7-24-2012

- Categorized in: 2012 Articles, Ten Greatest Jamaicans, Yearly ARCHIVES

When the white English missionary William Knibb was posthumously awarded the Order of Merit in 1988, Devon Dick wrote

‘No other person of his era demonstrated such faith in the prowess of the black people.

For Knibb's work as Liberator of the slaves;

For his work in laying the foundation of Nationhood;

For his support of black people and things indigenous;

For his display of great courage against tremendous odds;

For being an inspiration then and now.’

Knibb came to Jamaica in 1824 and grew into slavery’s most uncompromising enemy.

‘The cursed blast of slavery has, like a pestilence, withered almost every moral bloom. I know not how any person can feel a union with such a monster, such a child of hell. I feel a burning hatred against it and look upon it as one of the most odious monsters that ever disgraced the earth.’

He made enemies among slave owners, and was placed under armed guard during the 1831 Sam Sharpe Rebellion. The ‘Colonial Church Union’ burnt down his Falmouth chapel, plotted to murder him, and stoned his home. Under siege, the Baptists sent Knibb to Britain to report first hand the situation in Jamaica.

‘The anti-slavery feeling in Britain was not then widely diffused or intense. Knibb changed this by travelling six thousand miles in five months, attending 154 public services and addressing 200,000 people throughout Scotland, Ireland and England. No one else did a tenth of his work.’ [Dick]

The Baptist Missionary Society relied upon the goodwill of planters, and so did not openly support the emancipation movement, instructing missionaries not to interfere in civil affairs. Knibb’s speech at their public Annual Meeting on June 21, 1832 changed their stance.

‘I call upon children, by the cries of the infant slaves who I saw flogged… I call upon parents, by the blood streaming back of Catherine Williams , who… preferred a dungeon to the surrender of her honour. I call upon Christians by the lacerated back of William Black… whose back, a month after flogging, was not healed. I call upon you all, by the sympathies of Jesus’.

At this point, Mr Dyer, Secretary of the Society, pulled his tail coat by way of admonition. But Knibb continued:

‘Whatever may be the consequence, I will speak. At the risk of my connexion with the Society, and of all I hold dear, I will avow this… Lord, open the eyes of Christians in England, to see the evil of slavery and to banish it from the earth.’

There was thunderous applause, and Dyer himself proposed a public meeting as the next round in the struggle.

On August 15, 1832, in front of 3,000 Londoners, Knibb held up iron slave shackles and hurled them deafeningly to the floor:

‘All I ask is, that my African brother may stand in the same family of man; that my African sister shall, while she clasps her tender infant to her breast, be allowed to call it her own; that they both shall be allowed to bow their knees in prayer to that God who has made of one blood all nations as one flesh.’

Knibb’s unassailably authentic reports did more than any other source to convince Britons that slavery must be speedily abolished. Less than two years later, on August 1, 1834, it was theoretically terminated by Parliament. But slaves were supposed to endure a further six year 'apprenticeship' before gaining full freedom. Planters abused this provision, but the protests of Knibb and others prompted Parliament to bring forward full emancipation from to August 1, 1838.

In 1839, Knibb founded the weekly newspaper the Baptist Herald and Friend of Africa, giving freed slaves their own voice. He adopted James Phillipo’s ‘free village’ system, and helped raise money to purchase thousands of acres that enabled former slaves to own their own property. He also founded schools and organised teacher training.

On August 1, 1839 — 124 years before Martin Luther King’s ‘I have a dream’ speech — Knibb declared:

‘The same God who made the white made the black man. The same blood that runs in the white man's veins, flows in yours. It is not the complexion of the skin, but the complexion of character that makes the great difference between one man and another.’ (These words were inscribed on a plaque in the Falmouth Baptist Chapel)

Knibb was the first to see the electoral possibilities of grassroot political organisation, encouraging Baptist church members to endorse pro-slave candidates in the pre-abolition 1830s. When the franchise was broadened in 1840, he organised the black and coloured electorate to challenge the church establishment, creating a new awareness among common Jamaicans of their rights and latent electoral power.

When Knibb died of fever in November 1845, 8,000 mourners attended his funeral.

Kevin O'Brien Chang is managing director of Fontana Pharmacy and author of Jamaica Fi Real: Beauty, Vibes and Culture. Email: kobchang365@gmail.com. www.kevinobrienchang.com