Columns By Category

Popular Articles

- THE REALITY OF TACKY AND SAM SHARPE

- PLEASE DON’T BETRAY US AGAIN POLITICIANS

- CRY, MY MURDEROUS COUNTRY

- MODERNIZING THE PNP: VERSION.2020

- IS THE EXCHANGE RATE ON TARGET OR IS IT A WHOPPER?

- CARICOM: BEACON OF DEMOCRACY OR COWARDLY DISGRACE?

- DEMOCRACY PREVAILS IN THE UNITED STATES

- THE CRIME STATISTICS SPEAK FOR THEMSELVES

- PETROJAM, OIL PRICES, AND THE $7 TAX

- Kevin O'Brien Chang | Brains, not brutality – smart(phone) crime fighting

- TERRORISM IN JAMAICA

- STOP CURRENCY CRISIS TALK

- 'CASTIGATED KD' AND THE 9 YEAR WONDER

- GET PAST MERE TALK ON DONS AND GARRISONS

- LOW VOTER TURNOUT MYTHS AND ELECTION PREDICTIONS

- HOW GREAT CAN BROGAD BE?

- PNP WAS SOCIALIST FROM THE START

- AN AGE AND GENDER RE-ALIGNMENT ELECTION?

- Most influential Jamaican of 2010-2019?

- NO GAYLE, NO RUSSELL, NO TALLAWAHS

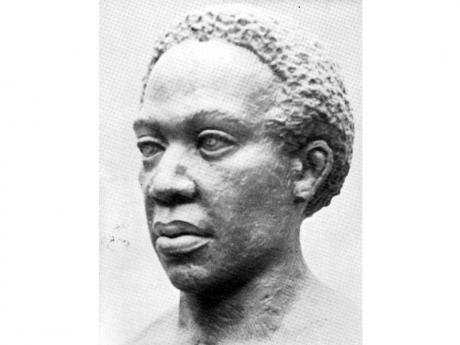

THE REALITY OF TACKY AND SAM SHARPE

- 10-19-2021

- Categorized in: 2021 Articles, Yearly ARCHIVES

Tacky's Revolt: The Story of an Atlantic Slave War

Vincent Brown

Island on Fire: The Revolt that Ended Slavery in the British Empire

Tom Zoellner

Modern research has reshaped interpretations of Jamaica’s past, especially the 1760-1761 slave rebellion. The revolt involving Tacky was but one episode in a greater three part Coromantee war involving separate actors. The initial April 1760 outbreak in St. Mary, led by Tacky, lasted but a week. A far bigger uprising took place in Westmoreland from May to July 1760, headed by Apongo, also called Wager. Then came a lower level but fear inducing guerrilla war led by Simon, ending in mid 1761.

Brown’s index contains 8 references to Tacky, 7 to Simon, and 26 to Apongo/Wager. Almost nothing but their names is known of Tacky and Simon, with Tacky said to mean 'royalty'. But Wager/Apongo was a West African military leader who had been a guest of British agent John Cope on the Gold Coast. Captured and sold during 1740s intra-African wars, Apongo became the property of Captain Arthur Forrest of HMS Wager, hence his name. Wager came to Forrest's plantation in Westmoreland, where he again encountered John Cope, now a Jamaican estate owner.

Cope occasionally entertained his former acquaintance Apongo, laying a table and treating him as a man of honor, insinuating that he would be repatriated when absentee owner Forester returned. Their understanding did not outlast Cope's 1756 death. Apongo began plotting a war against whites, awaiting an opportune moment to strike.

Plantation owner and historian Edward Long, created an unreliable chronology painting Tacky as overall chief of the widespread conspiracies. He tried to rebut allegations that the rebellions resulted from mistreatment and mismanagement. Rebelliousness was a criminal trait of Coromantees, Long asserted, and Africans ‘deserve to be exterminated from the earth’. His pathological racism perhaps still infects white political imaginations.

Bryan Edwards, the era’s other main historian, wrote the poem 'Stanzas, Occasioned by the Death of Alico, an African Slave, condemned for Rebellion in Jamaica, a.k.a. 1760’. It referenced Tacky's Revolt and eulogized the rebel ‘Abruco, aka Blackwall’, as a symbol of the struggle for liberty.

"Firm and unmov'd am I/ In freedom's cause I bar'd my breast/ In freedom's cause I die...”

Abolitionist activists were quoting this poem to rebuke slaveholders in the 1780s. But by then Edwards had become an owner and ardent defender of slavery.

Both Long's fear and Edwards' admiration of Coromantees originated in the same idea. Namely that Gold Coast Africans were distinguished by an intrinsic cultural essence that might define something fundamental about blacks in general. The martial masculinity, haughty pride, and relentless daring for which 18th century Coromantees were noted, has ever since thrilled and frightened whites, and parodied and beckoned to black men.

Jamaican insurrections inspired racist reactions, but also forced colonial slavery reform by concerned Britons fearing further rebellion. They pragmatically enhanced colonial security by limiting dependence on the slave trade and ameliorating the conditions of slavery. Ironically and perversely, Edward Long’s racism significantly spurred a budding anti-slavery discourse.

The 1760-61 rebellion was the greatest British Empire uprising before the American Revolution. It perhaps even provided indirect inspiration. A tantalizing question lingers: if Maroons not fought against slaves and instead joined them, might the Jamaican Coromantee Wars have overthrown the island’s plantation slavery system?

Island On Fire gives the full documented story of the Sam Sharpe Christmas War. It covers the reality of Jamaican slavery, the genesis and unfolding of the revolt, the island aftermath, and its critical impact on the British slavery debate.

It convincingly argues that Sharpe's December 1831 Rebellion was perhaps the single most important event in creating the mindset that led, less than 2 years later, to the 1833 Slavery Abolition Act.

William L. Green wrote in British Slave Emancipation: "It was the Jamaican rebellion, not the new vigor of the anti-slavery movement, that proved a decisive factor in precipitating emancipation."

As a conduit between the Colonial Office and Parliament, diplomat Henry Taylor was especially well positioned to assess the political effect of Sharpe's rebellion. To him, "This terrible event, with all its horrors and cruelties, military slaughters and many murders by flogging, though failing at its object as a direct means, was an indirect death-blow to slavery."

William Knibb argued that if the British public gave enslaved Africans as much credit as it did Europeans, they ought to erect a statue of Sharpe as the avatar of Jamaican freedom.

In Massachusetts, Henry Bleby was loudly applauded when he called Sharpe ‘the original author of British emancipation’, noting that his revolt and its vengeful aftermath had become the tipping point for government action. "It was this storm of indignation raised among the British people, that led to the abolition of slavery."

Sharpe told Bleby he was sorry that the sugar estates had been burned and so many people killed. His only goal had been to free his people, and what had been a peaceful movement spun out of control. But he remained defiant about the idealism of his cause: "I would rather die upon yonder gallows than live in slavery!" When Sharpe said this, reported Bleby, his frame expanded, his spine stiffened, and his eyes seemed to "shoot forth rays of light".

Abolishing slavery in the British empire set in motion forces that could not be contained, and would in the end, end official slavery across the planet for the first time in recorded history. No Sam Sharpe Rebellion, no British 1838 emancipation. And perhaps no France 1848, US 1865, Spain 1867, Brazil 1888 etc abolitions.

Few Jamaicans however, realize what a truly world changing figure Sam Sharpe was, or know anything of Apongo. But how could we, when history is no longer taught in schools as a separate subject, and there is no book that gives an accurate, up to date narrative of the country’s past?

Our knowledge of the 1760-61 and 1831-32 uprisings is still shaped by the 1958 colonial minded ‘History of Jamaica’ by Clinton Black. The most recent overview of the island’s past is the patchy ‘The Story of the Jamaican People’ by Phillip Sherlock and Hazel Bennett, written in 1998.

We need to re-examine our received notions of the role played in our national formation by individuals like Tacky, Apongo and Sharpe. Which will clearly require giving Jamaican history a much more prominent role in both Primary and Secondary curriculums.

A national committee dedicated to keeping up on the latest developments in Jamaican history is also required. Their findings could then be publicly disseminated using all available mechanisms: public memorials, mainstream media, social media. And of course, an updated modern narrative of the full Jamaican experience has to be written.

Until then, Marcus Garvey’s assertion that “A people without the knowledge of their past history, origin and culture is like a tree without roots” will continue to ring all too true.

Kob.chang@fontanapharmacy.com