Columns By Category

Popular Articles

- THE REALITY OF TACKY AND SAM SHARPE

- PLEASE DON’T BETRAY US AGAIN POLITICIANS

- CRY, MY MURDEROUS COUNTRY

- MODERNIZING THE PNP: VERSION.2020

- IS THE EXCHANGE RATE ON TARGET OR IS IT A WHOPPER?

- CARICOM: BEACON OF DEMOCRACY OR COWARDLY DISGRACE?

- DEMOCRACY PREVAILS IN THE UNITED STATES

- THE CRIME STATISTICS SPEAK FOR THEMSELVES

- PETROJAM, OIL PRICES, AND THE $7 TAX

- Kevin O'Brien Chang | Brains, not brutality – smart(phone) crime fighting

- TERRORISM IN JAMAICA

- STOP CURRENCY CRISIS TALK

- 'CASTIGATED KD' AND THE 9 YEAR WONDER

- GET PAST MERE TALK ON DONS AND GARRISONS

- LOW VOTER TURNOUT MYTHS AND ELECTION PREDICTIONS

- HOW GREAT CAN BROGAD BE?

- PNP WAS SOCIALIST FROM THE START

- AN AGE AND GENDER RE-ALIGNMENT ELECTION?

- Most influential Jamaican of 2010-2019?

- NO GAYLE, NO RUSSELL, NO TALLAWAHS

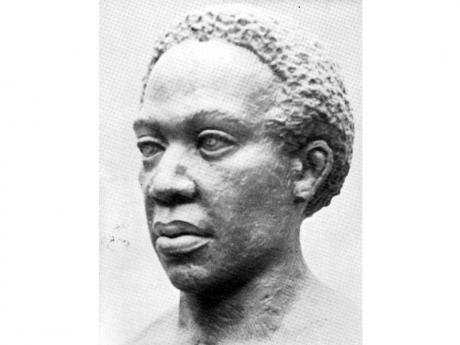

SAM SHARPE EMANCIPATION HERO

- 7-27-2012

- Categorized in: 2012 Articles, Ten Greatest Jamaicans, Yearly ARCHIVES

THE OUTSTANDING leader of the 1831 Christmas slave revolt, often referred to as the 'Baptist War' because of the denomination of most participants, was Deacon Samuel 'Daddy' Sharpe.

Wesleyan missionary Henry Bleby described him as the most remarkable and intelligent slave he had ever met.

Sharpe argued that the Bible proclaimed the natural equality of men, and denied the right of whites to hold blacks in bondage. He persistently quoted the text, 'No man can serve two masters', which became a slogan among slaves. Sharpe also read newspapers of the day, and came to believe that Britain had freed the slaves, or planned to do so. His sense of urgency was also fuelled by violently anti-abolitionist planters, who openly talked of joining the United States as a slave state, thus postponing emancipation indefinitely. Rumours even spread among slaves that whites planned to kill all black men and keep the women and children in bondage.

What Sharpe had envisaged, a century before Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King, was a movement of passive resistance, a sit down strike of all the slaves in the western parishes. He hoped to force the plantation owners to pay them for their work, and thus affirm their freedom. Drivers on each estate were delegated to tell overseers returning from the three-day Christmas holidays that slaves would work no more without wages.

Fight for their freedom

However, if an attempt was made to force them back to the fields as slaves, they would fight for their freedom. To this end, a black regiment about 150-strong was formed, with 50 guns among them, led by Thomas Dove and Robert Gardiner. It was believed that royal troops would not fight the slaves whom the king had freed, so only the planter militia might challenge them in the field. No one was to be killed, except in self-defence. Word was spread in nightly prayer meetings, and Sharpe swore conspirators to secrecy by asking them to 'kiss the book'.

However, rumours reached the planters. Troops were sent into St James in case of trouble, and warships were anchored in the harbour. On the last night of the holidays December 27, the occupants of Kensington Great House fled to Montego Bay, and the St James militia marched on the estate to ensure slaves returned to work. The slaves reacted to the militia's presence by setting fire to Kensington estate, which was located on the highest hill in St James. By midnight, 16 other western estates were burning, and a rebellion was on the way, led by some of Sharpe's most trusted lieutenants.

The rebels routed the first militia that confronted them, and roamed over the countryside, destroying plantations. Terrified planters and their families fled, leaving 50,000 slaves suddenly freed and uncertain what to do. Sharpe moved among the estates, counselling and praying, but matters were now beyond his control. Martial law was declared, and the untrained and uncoordinated rebel forces were soon overwhelmed by superior military force. Armed resistance was virtually at an end by the first week of January.

Though property destruction was widespread, loss of life was very low, and even armed rebels fought only against whites who attacked them. Those offering no opposition met with no harm, and there were only two acts of violence against whites throughout. This restraint was noted by a Presbyterian missionary:

"Had the masters when they got the upper hand been as forbearing, as tender of their slaves' lives as their slaves had been of theirs, it would have been to their lasting honour, and to the permanent advantage of the colony".

The civil authorities retaliated brutally. While fewer than 20 whites were killed in the revolt, nearly 600 slaves were executed in its aftermath. Perhaps influenced by the jailing of white missionaries like William Knibb and Thomas Burchell, Sam Sharpe gave himself up to the authorities. He admitted responsibility, cleared the missionaries of any blame, and said destruction of life and property was not part of his plan.

Road to freedom

Even in jail he never lost his composure, praying and preaching to his fellow prisoners. On May 23, 1832, he was hanged, having told Bleby, 'I would rather die upon yonder gallows than live in slavery.' His body is said to have been removed from its original burial place to a grave beneath the pulpit of the Montego Bay Baptist Church. The location of his gallows is now the Sam Sharpe Square in Montego Bay.

Although an ostensible failure, Sam Sharpe's rebellion was the final hammer blow on the door to freedom. If moral arguments were not sufficient, the threat of more such rebellions made slavery obviously untenable. On August 29, 1833, less than two years after Sharpe's death, the House of Commons passed the bill to free all British Empire slaves.

Kevin O'Brien Chang is managing director of Fontana Pharmacy and author of 'Jamaica Fi Real: Beauty, Vibes and Culture'. Send feedback to kobchang365@gmail.com. www.kevinobrienchang.com.