Columns By Category

Popular Articles

- THE REALITY OF TACKY AND SAM SHARPE

- PLEASE DON’T BETRAY US AGAIN POLITICIANS

- CRY, MY MURDEROUS COUNTRY

- MODERNIZING THE PNP: VERSION.2020

- IS THE EXCHANGE RATE ON TARGET OR IS IT A WHOPPER?

- CARICOM: BEACON OF DEMOCRACY OR COWARDLY DISGRACE?

- DEMOCRACY PREVAILS IN THE UNITED STATES

- THE CRIME STATISTICS SPEAK FOR THEMSELVES

- PETROJAM, OIL PRICES, AND THE $7 TAX

- Kevin O'Brien Chang | Brains, not brutality – smart(phone) crime fighting

- TERRORISM IN JAMAICA

- STOP CURRENCY CRISIS TALK

- 'CASTIGATED KD' AND THE 9 YEAR WONDER

- GET PAST MERE TALK ON DONS AND GARRISONS

- LOW VOTER TURNOUT MYTHS AND ELECTION PREDICTIONS

- HOW GREAT CAN BROGAD BE?

- PNP WAS SOCIALIST FROM THE START

- AN AGE AND GENDER RE-ALIGNMENT ELECTION?

- Most influential Jamaican of 2010-2019?

- NO GAYLE, NO RUSSELL, NO TALLAWAHS

The Road to a Cruel Jamaica

- 6-13-2010

- Categorized in: 2010 Articles, Jamaica

http://jamaica-gleaner.com/gleaner/20100613/focus/focus2.html

Published: Sunday | June 13, 2010

Kevin O'Brien Chang, Gleaner Writer

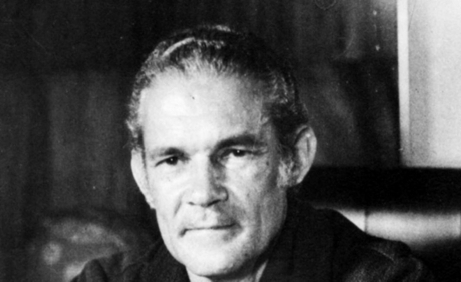

'How easy it is if an example is set by Government of cruel conduct, for everybody to condone cruelty and for cruelty to become a national attribute.'

—Norman Manley, 1966

BETWEEN 1962 and 2009 Jamaica's murder rate went from 3.9 to 62.2 per 100,000 - perhaps the greatest violent death rate increase experienced by any country not at war. How did we get here?

Recent books give varying perspectives, including Edward Seaga's My Life and Leadership, Patrick E. Bryan's Edward Seaga, and Amanda Sives' Elections, Violence and the Democratic Process in Jamaica 1944-2007. Obika Gray's 2004 Demeaned But Empowered covers similar ground.

Sives and Gray date modern Jamaican politics from 1944, losing the crucial context of the 1938 upheavals. Sives calls Alexander Bustamante a "self-proclaimed friend of the workers" who aroused loyalty mainly through the "role of personality". Yet Bustamante inspired legendary devotion because of his commitment to workers' welfare, even proclaiming to levelled police bayonets: "Shoot me, but leave these defenceless, hungry people alone."

Britain was a 'gentler' colonial master than Germany, Spain or France. Yet protesting workers were shot dead at Frome in 1938, and when St. William Grant, Bustamante's lieutenant, was arrested on May 24th, "The police made a pulp of Grant's head and underneath his private parts ... . He had never been the Grant he was before that, again, until he died" (Bustamante: Notes, Quotes, Anecdotes, Ken Jones, page 53).

Confronted with colonial brute force, the Bustamante-led workers no doubt responded with brute force. Wills O. Isaacs has been pilloried for asking, "What are a few broken skulls in the building of a nation?" Yet revolution is not a tea party, and nationhood comes mainly from the barrel of a gun. Compared to most other Third World countries, Jamaica's political development from 1938 to 1962 was unusual for its relative lack of violence.

Nations are generally born in chaos and mature into settled democracies. Jamaica's peacefully attained political stability then saw violence relentlessly increase. What caused this?

Maybe the 'British overlordship democracy' of 1944 to 1962 was a quasi-dictatorship that stifled legitimate underclass grievances, which exploded into violence when independence removed artificial colonial restraints. Or perhaps the statesmanship of Alexander Bustamante and Norman Manley drew lines not to be crossed, which less-principled successors failed to respect.

Comparative history supports the latter view. Few other colonial territories saw anything like Jamaica's remarkably smooth transition from widespread unrest in 1938 to peaceful elections in 1944 to unchallenged regime changes in 1955 and 1962. After his 1955 election loss, Bustamante telegraphed Norman Manley: "We shall be an honest opposition. Good luck." When age caused both to leave the stage, it became 'blood for blood, fire for fire'.

Murders in Jamaica soared by 69 per cent from 1965 to 1966, with the largest increase in the West Kingston constituency of Member of Parliament Seaga and challenger Dudley Thompson. The July 1966 levelling of Back O' Wall was a defining event. In Edward Seaga's account, Back O'Wall ... was the worst crime den in the country ... a den of support for the PNP (People's National Party) ... [gunmen and thieves] brought with them the criminal and violent activity... they wanted ... to cripple ... my presence in the area so as to reassert their dominance which would allow them to do what they want" [Sives page 66].

"They [Jamaica Labour Party (JLP)] supporters were being gunned down ... I built for them what people call an enclave, and I make no apology for that, so they could walk in peace and that their daughters wouldn't be raped ... " [Sives page 136].

On July 26, 1966, Norman Manley spoke thus in Parliament:

"The level that separates normal, human, decent conduct ... from what is virtually obscene cruelty is a very narrow margin indeed ... how easy it is if an example is set by Government of cruel conduct, for everybody to condone cruelty and for cruelty to become a national attribute ... when I hear [acting Prime Minister Donald Sangster] argue that because squatting is illegal ... and a few people had behaved violently and threw sticks of dynamite, therefore you are ... justified in destroying people's personal property, in leaving people shelterless, with their children, to sit in the rain and to sleep on graves. And so many of the comfortable middle class sat on their verandas ... and justified the action of the Government ... . This thing has driven deeper divisions than ever between one class whom we regard as sufferers and others who are more comfortable ..." [Bryan, page 155].

Terry Lacey's Violence and Politics in Jamaica: 1960-1970 [pages 131-137] is sad déjà vu reading.

"There were two new features of the JLP-PNP rivalry in Western Kingston. First, the widespread use of firearms and second, the reluctance of the police to arrest known gunmen ... . They were now reluctant to raid in Western Kingston because of the amount of firepower in the area." [Lacey]

"... When a state of emergency was declared and the army and police moved in strength into Western Kingston, The Gleaner commented, 'At last'. 'No wonder these criminal pests have been going round the suburbs as well as the slums behaving like the new lords of the jungle! They knew that, more often than not, just as soon as they were arrested, some politician would ... bail them out'."

Under siege

In 1966, the PNP held eight of 10 urban constituencies, the exceptions being Seaga's West Kingston and D.C. Tavares' South West St Andrew. From one viewpoint, these JLP enclaves were under siege from rampant PNP forces intent on total city domination, with implicit police support - 65 per cent of the security forces voted PNP in 1967. Had Seaga not fought back in kind, he would have been driven out by force, making the Corporate Area, and perhaps later the entire island, a one-party entity.

Another perspective says Seaga's party held state power, and a properly marshalled military could have achieved a relatively peaceful status quo. He used unprecedented means, as the October 1966 state of emergency, to establish an independent power base, impregnable even to his own governing party.

Posterity will choose its 'official' narrative, but if Edward Seaga did indeed bring a new ruthlessness to Jamaican politics, Michael Manley was fully his equal.

"... Garrison-style voting was not apparent in West Kingston until 1972 ... . Credit for this unfortunate result was no doubt due to the ... martial preparedness of Edward Seaga ... . Likewise ... the infamous Garrison gang, a group of PNP toughs, carried out acts of intimidation and perpetrated violence and mayhem on behalf of constituency representative, Michael Manley. This group ... was apparently so effective in expelling JLP threats in Central Kingston in 1967 and 1972 that Manley ... at a public rally late in 1974 commended the enforcers by their popular names: "I thank the Central Kingston Executive. I thank my Paseros of the Garrison - Skully, Val, Boots, Vinnie, Burry, Bernard, Spar, as a glory." [Gray pages 150-151]

Prime Minister Manley and several Cabinet members led 20,000 mourners at Winston 'Burry Boy' Blake's March 1975 funeral. [Gray page 187]

Did Edward Seaga and Michael Manley personally alter the fabric of Jamaican politics or were they merely agents of inevitable historical forces? Had Donald Sangster not died of a brain aneurism in 1967, and had Vivian Blake won most votes at the 1967 PNP leadership conference, would Jamaica be a less-cruel nation today?

We will never know. But Lacey's 1977 book ends with depressing familiarity:

"A generation of Jamaican youth has probably been lost for development and compromises a tragic social problem and a security risk as long as a youthful dispossessed lumpenproletariat hangs about the streets of Kingston doing nothing. The same thing must not be allowed to happen to the next generation of Jamaican schoolchildren."